Using evidence to guide inpatient care delivery as a team for high-quality patient outcomes.

Ryan Schwieterman, MD

Posted: 9/9/2024

As healthcare evolves, the limitations of care delivery and patient outcomes become better understood, yet simultaneously more complex. The healthcare world, in some ways, has much to learn from the business world particularly around process and efficiency. I am sharing with you the perspective and hypothesis that efforts to improve efficiency can significantly improve several healthcare outcomes for patients and have been linked to improved satisfaction with providers and improved learning for residents. From the patient perspective, people want to be heard, they want to trust, they want to feel safe, they want to understand, they want to feel in control, and they want to get out. The hospital is an inherently non-conducive environment for these core needs. By implementing a bundled approach, a hospitalist team can improve and stabilize the critical aspects that go into achieving these core needs, namely: consistently aligned communication, efficiency of care, and reduced waste (time and dollars). A bundled intervention that addresses this is Strategic Interdisciplinary Geographic Bedside Rounds (SIGBR) with Rounding In-Flow practices utilizing checklists and dedicated handoff processes. I will define these practices and share with you the evidence demonstrating the clinical effectiveness of these approaches and how they have successfully induced significant improvement amongst several quality metrics as well as provider satisfaction and resident learning experiences.

Bundled Intervention:

Combining what works into one approach

In modern hospital settings, improving patient care and team efficiency is essential, and several key interventions have been implemented to achieve these goals. One such intervention is Interdisciplinary Bedside Rounds, where healthcare professionals—including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and case managers—gather at the patient’s bedside to collaboratively discuss the care plan. This approach fosters a direct and open exchange of information with the patient, allowing for real-time clarification of any outstanding issues and promoting shared decision-making.9,11 Studies, such as the one by Starmer AJ, et al., have demonstrated that such structured communication can significantly reduce medical errors and preventable adverse events, ultimately enhancing patient safety without negatively impacting workflow.1

Another intervention, Geographic Rounding, localizes patients from a physician’s team to the same hospital unit, improving efficiency by fostering better communication and collaboration between staff. This method ensures more frequent interactions between the care team members as well as consultants who often need to round on patients throughout the hospital. This assists in reducing delays in care delivery. Geographic rounding enables teams to communicate more fluidly throughout a workday. This is because the individuals of the team are all within a specific location which allows for frequent micro-information exchanges to occur outside of dedicated interdisciplinary rounds. Additionally, there is standardization of workflows amongst team members after they grow accustomed to their typical workflows and better understand each other’s needs. Research by Williams A, et al., has shown that geographic rounding can significantly reduce rapid response rates, enhancing the overall safety and responsiveness of inpatient care.7

Inpatient healthcare teams are made up of physicians, residents, medical students, pharmacist, nurses, techs, case managers, social workers, PT, OT, SLP, patients, and their families. Each player on the team has critical roles to carry out for the patient. The challenge of unified workflows is that each player on the team has schedules and other responsibilities that likely do not align with the other players on the team. For example, physicians may round at 9 AM but nurses are passing medication. Case management would like the plan for the day by 9 AM but the physicians haven’t seen any patients yet. Also, residents are practicing and learning at the same time which may require them to be in other locations or fulfilling other program responsibilities, further delaying the communication of care. Additionally, each patient has their individual phases of care dependent on their pathology, their response to treatment, their baseline functional capacity, comorbid conditions and their management, and underlying socioeconomic factors. All of these must be considered when assessing a patient’s readiness for discharge and each element is best assessed by varying members of the medical team. Currently, most communication occurs through progress notes and perfect serve. From the physician perspective, a physician may have to wait for the opinions or information updates of PT/OT/SLP/CM/SW/Nursing before feeling a patient is adequately ready for discharge. Not to mention the opinion of consultants. Reasonably, some of these opinions can be estimated safely and some are identified earlier in the stay and thus aren’t inhibiting discharge. Further, establishing next phases of care often requires coordination with numerous outside hospital entities. By combining strategic interdisciplinary bedside rounds with geographic rounds (SIGBR), these silos can be mitigated, and the flow of care can occur more efficiently.

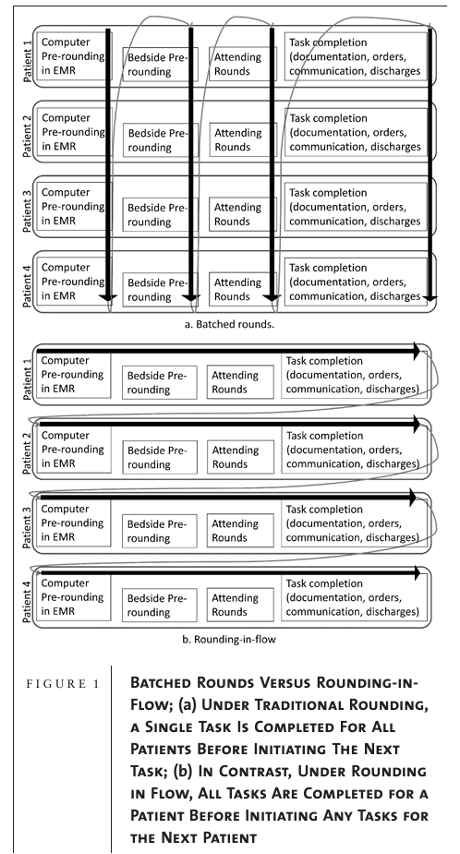

In a further step towards operational efficiency, Rounding-In-Flow employs a lean methodology, focusing on completing all tasks for one patient before moving on to the next. This contrasts with traditional batch rounding, which often leads to inefficiencies. Calderon et al. demonstrated that this method improved care delivery by reducing patient length of stay and enhancing workflow efficiency. Rounding-in-flow saves several hours per day for the patient. No longer does the patient have to wait for computer pre-rounds and resident bed-side rounds before the final decisions may be made during Attending Rounds. Additionally, other members of the medical team don’t have to wait for physicians to pre-round as it would be done outside the room with the care team. Furthermore, batched rounding styles occur later in the day, forcing discussion to be compressed before lunch or other conflicting responsibilities. This is also a time of day when patient care is ramping up causing an increase in rounding interruptions which leads to an increase in task switching and cognitive load (where flow slows down, focus is interrupted, details are missed, and mistakes happen).4,5

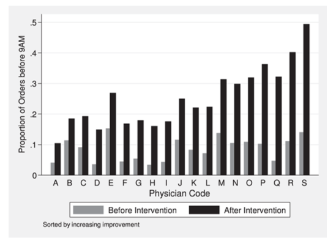

Timely Discharge Orders by Attending Hospitalists in Intervention Groupa

a More than 25 discharges before the intervention and 25 discharges after the intervention (total N = 5210 discharges for 19 hospitalists, mean = 274, range = 139–453). All differences were significant (P < .05), except physician B (P = .13).

By adopting rounding-in-flow, hospitals can ensure that patient care is more structured and thorough, minimizing errors and delays.

These interventions are often supplemented using Rounding Checklists, which ensure that all critical steps in patient care are completed during rounds, leaving little room for omission of important tasks. These checklists serve as cognitive aids, particularly in high-stress environments, further improving patient outcomes by standardizing care procedures.

Rounding Checklist Example

LDA: [ ]CVC / [ ]PICC / [ ]Midline / [ ]Foley / [ ]Drains / [ ]Mediport / [ ]None

Antibiotics: Antibiotic, indication, Duration, Cultures?

Steroids: Indication, duration?

Labs (still needed?): [ ]Yes / [ ]No

IVF (still needed?): [ ]Yes / [ ]No

Level of care: [ ]Step Down / [ ]Med-Surg

Bed Status: [ ]Inpatient / [ ]Observation

Telemetry: [ ]Yes / [ ]No

PT/OT: [ ]Yes / [ ]No

DVT Prophylaxis: [ ] Lovenox / [ ] Heparin / [ ] SCDs / [ ] Already on Systemic Anticoagulation / [ ] None

Consultants Updated?

Finally, a critical element in improving continuity of care is dedicated Handoff Processes for different transitions, such as in-hospital transfers, overnight handoffs, and end-of-service handoffs. As demonstrated by Schram et al., introducing standardized handoff templates—such as the IPASS template—addresses gaps in communication during these transitions, resulting in smoother care transitions and better patient outcomes. Implementation of standard handoff processes has been shown to be confidence building in providers taking over and has also shown to be neutral regarding time spent. Handoffs take time to do but save time in the long run and increase provider and patient confidence.

These evidence-based practices, each supported by significant research, show the potential to not only streamline the process of medical care but also enhance patient safety and improve educational outcomes in clinical settings. By adopting these interventions, hospitals can provide higher-quality care and ensure that clinical teaching remains robust and effective for future healthcare professionals.

Conclusion:

By implementing strategic interdisciplinary geographic bedside rounds (SIGBR) with rounding-in-flow, supported by dedicated handoff processes and checklists, healthcare teams can significantly improve patient outcomes, reduce errors, and enhance the overall experience for both patients and providers. The evidence is clear: adopting these efficiency-driven, patient-centered strategies leads to lower mortality rates, reduced length of stay, and fewer rapid responses, while also boosting team communication and resident satisfaction.6-10

Healthcare is evolving, and hospitals must evolve with it. Efficiency is not just about saving time—it’s about improving quality, reducing harm, and creating an environment where patients feel heard, cared for, and in control of their treatment. These interventions also empower healthcare teams to function more cohesively, ensuring that each member can focus on what they do best.

Looking forward, the adoption of these practices should not be seen as optional but as essential steps toward modernizing healthcare delivery. By continually refining processes and learning from each implementation, hospitals can ensure they are meeting the highest standards of care. As the healthcare landscape continues to grow more complex, embracing these evidence-based strategies will position hospitals to thrive, ensuring better outcomes for patients and a more sustainable, satisfying work environment for providers and learners.

Sample Rounding Day

7:00 AM:

Residents get handoff from night team. Hospitalists get handoff from night team. Teams pick up printed list from work room. Night residents staff admissions with attendings.

Nurses get handoff

Case Management prepares for rounds.

7:30 AM: In-Flow rounding begins. Start with sick patients. Protected time. NO MEETINGS. NO ADMISSIONS.

Attended by Physicians, Residents, Medical Students, Nurse, Case Management, Social Work

- Overnight report from nurse

- Overnight report from resident

- Review labs, imaging, and vitals

- Develop preliminary Assessment and Problem List

- See patient: Attending is there for support and clarification.

- Introduce if first time

- Resident leads discussion with patient

- Patient Assessment

- Remainder of team asks their questions

- Patient/Family ask their questions.

- Resident summarizes plan

- Team exits

- Orders are entered

- Check list followed

- Consultants updated via perfectserve

- Learning List updated. Brief discussion if time allows.

Repeat for entire list. Approximately 10-15 minutes per patient.

10:30 AM: Rounding completed. Physician team assess for any updates that occurred during rounds. Orders are reviewed and further follow up with consultants as needed. Begin writing progress notes, discharge summaries, and virtual handoffs. Given verbal handoffs if patient transfers from your unit. Receive verbal handoff if patient transfers to your unit. If you did not have case management or social work present during rounds, now is your time to run the list. Meetings and admissions now acceptable.

12:00 PM: Lunch

1:00 PM: Afternoon central IDR. Updates, plan for tomorrow.

Rest of day: Education, finish notes, follow up with consultants, run the list with attending, finish virtual handoff.

7:00 PM: IPASS Handoff to night teams.

FAQ:

Q: Won’t geographic rounds lead to more handoff’s and don’t handoff’s pose risk for medical errors?

A: Yes, if a patient needs to transfer to another unit, a handoff will need to occur. The problems surrounding handoffs are related to lack of handoff process. When handoff process is in place, evidence shows that errors are reduced and time spent ‘learning’ the patient is also reduced. This also contributes to consistency of communication which patients value, not to mention reduction of errors. 1,2

Q: Won’t an increase in handoffs negatively impact my learning as a resident?

A: No, when executed properly, residents have previously reported increased satisfaction with their rotation experience. In combination with handoff process and in-flow rounding. It is predicted that residents will find more time for learning or other task management outside of their work due to efficiency gains from the bundled intervention.

Q: How can a case manager perform bedside interdisciplinary rounds when they have 25 patients and the hospitalist has 15?

A: Split the list. Day 1, round with Hospitalist Team A and Hospitalist Team B will run the list with you after your rounds. Which will likely be around 10 AM. Flip the teams each day.

Q: Won’t my learning be compromised if we are looking patients up together and I am presenting on the fly?

A: No, you are learning meta skills including thinking on your feet, rapid processing of information, effective communication and collaboration, increased efficiency. You are reducing risk for error by not forgetting details you picked up in pre-rounds. You are creating more time for yourself later to focus on direct patient care, learning, task completion, and other life management.

Q: What about discussions had during table rounds?

A: Discussions are effective ways to learn the ‘pro-tips’ not taught in books and serve as great supplements to learning. Small discussions can occur particularly when speaking with the patient. Otherwise, by increasing efficiency during rounds there is increased time for discussion outside of rounds. I recommend keeping a ‘Learning List’ during rounds to follow up on topics later in the day or week.

Q: Won’t I be having more ‘Day 1’ encounters and thus have more work to do?

A: See the associated literature. Handoffs take time but save time too and have been shown to be neutral to total work time. Additionally, the increased efficiency obtained through the bundled intervention will further save you and your patients time.

Q: What about if a family has tons of questions or if a patient is rambling?

A: Sometimes there are clinical scenarios that warrant additional time or dedicated family meetings. Those should be scheduled for later in the day otherwise they are impacting the care for the rest of your patient list. Adequately answer the pertinent questions in the moment and share the care plan. Otherwise, offer to schedule a dedicated meeting later in the day. If it is an overbearing family being unnecessarily complicated, follow the same script but assert your responsibility to care for the rest of your patients.

Q: Won’t hospitalist have uneven numbers of their patient panel?

A: Very likely. To do what is best for patients will likely cause imbalance in patient loads. Much like handoffs, you need to zoom out and see the ‘net’. If provider A starts with 17 and provider B starts with 12 then provider B will reasonably be early on the list for admissions if the admission team gets busy later in the day while Provider A will be at the back of the list. It would likely be reasonable to give provider B two admits before giving provider A any. Also, if a provider is low on patients, that likely means they have room on their unit which would increase the likelihood of them keeping an admission by requesting the hub place the patient on their unit. In the end, it isn’t possible to predict every scenario, which is why we rely on our team of professionals to assess each situation and make the best decision they can in the moment.

Q: Early/Late team has been a strong retention tool. Won’t this impact it?

A: Doesn’t have to. Early/late team, early-out, round-and-go, is a concept at many hospitals around the country. It’s important that we support flexibility if we are going to be responsible for human lives for 84 hours out of a week. So, we aren’t entirely unique by having that structure. If admission flow proves to be complicated with the bundled interventions; early late may need adjusted. But it doesn’t need to go away, nor should it.

Q: What do I do during In-flow Rounding if I’m not needed?

A: This could occur for many team members. A patient may have zero case management/social work needs, etc. Look at your list of to-do’s, pick something that can be done quickly without much thought. Update a chart, send a perfect serve, update a handoff note. Our day is filled with small cognitive burden tasks, utilize your time well. Don’t do any of that if your time spent listening to the discussion could better help you take care of the patient. Sometimes we need to just listen. If we do these things well, collectively, things will move so much more efficiently. Pages will go down, questions will decrease, care will flow more efficiently.

Q: Can you really only spend 10-15 minutes with a patient and accomplish all necessary goals?

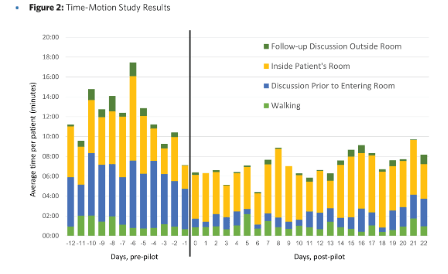

A: Yes, you can. When entering with a plan, you can accomplish quite a bit within a brief period. See this figure from a similar intervention carried out at UNC. You’ll notice that post intervention they averaged less than 10 minutes in a room on average. They did not use in-flow rounding though, hence the bump in time.

IMPLEMENTING PATIENT CENTERED MULTIDISCIPLINARY BEDSIDE ROUNDS 11

Q: How will we know if it is working?

A: We will monitor standard quality metrics such as mortality, length of stay, number of rapid responses, readmissions, patient experience, foley-catheter utilization, CVC days.

Appendices and References:

- Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1803-1812. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1405556

The study found that after implementing a handoff program in 10,740 patient admissions, medical errors decreased by 23%, and preventable adverse events decreased by 30%. However, non-preventable adverse events remained unchanged. Six of nine sites showed significant reductions in errors. Improvements were also seen in the inclusion of key elements in written and oral handoffs. There were no significant changes in the duration of handoffs or resident workflow, including patient-family contact and computer time. Overall, the handoff program reduced errors and improved communication without negatively affecting workflow.

2. Schram, AW; Cerasale, MT. REDESIGNING END-OF-SERVICE HANDOFFS: A STANDARDIZED APPROACH. Abstract published at Hospital Medicine 2020, Virtual Competition. Abstract 462. Journal of Hospital Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.13090

A large hospital medicine group implemented a modified IPASS template for overnight cross-coverage of patients but found it lacking in information for seamless end-of-service transitions. To address this, they designed a new template highlighting discharge disposition, outstanding hospital issues, timing of discharge, and key tasks for the next day. The new template was piloted and rolled out across services in 2019. While no significant time differences were noted in preparing handoffs or extra time spent in the hospital, providers reported increased confidence in discharge plans (6.56 vs. 5.57, p=0.06) and described an easier first day on service. The new template improved handoff quality, with further research recommended on its effects on patient safety and length of stay.

3. Calderon AS, Blackmore CC, Williams BL, et al. Transforming Ward Rounds Through Rounding-in-Flow. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):750-755. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-13-00324.1

A novel “Rounding-in-Flow” approach, based on Lean principles, was developed to have the patient care team complete all tasks for a single patient before moving to the next. A retrospective cohort study evaluated 17,376 inpatients and medical ward teams. Results showed an increase in timely discharge orders written before 9:00 am (from 8.6% to 26.6%), fewer resident duty hour violations (from 2.96 to 0.98 per intern per rotation), and a slight reduction in average daily intern work hours (from 12.3 to 11.9 hours). However, actual patient discharge times remained unchanged. The approach improved efficiency without increasing work hours.

4. Skaugset LM, Farrell S, Carney M, et al. Can You Multitask? Evidence and Limitations of Task Switching and Multitasking in Emergency Medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(2):189-195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.10.003

Emergency physicians work in a fast-paced environment that is characterized by frequent interruptions and the expectation that they will perform multiple tasks efficiently and without error while maintaining oversight of the entire emergency department. However, there is a lack of definition and understanding of the behaviors that constitute effective task switching and multitasking, as well as how to improve these skills. This article reviews the literature on task switching and multitasking in a variety of disciplines-including cognitive science, human factors engineering, business, and medicine-to define and describe the successful performance of task switching and multitasking in emergency medicine. Multitasking, defined as the performance of two tasks simultaneously, is not possible except when behaviors become completely automatic; instead, physicians rapidly switch between small tasks. This task switching causes disruption in the primary task and may contribute to error. A framework is described to enhance the understanding and practice of these behaviors.

5. Westbrook JI, Raban MZ, Walter SR, et al. Task errors by emergency physicians are associated with interruptions, multitasking, fatigue and working memory capacity: a prospective, direct observation study. BMJ Quality & Safety 2018;27:655-663. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007333

This study examined the impact of interruptions, multitasking, and sleep on prescribing errors among emergency physicians. Over 120 hours of observation, 36 physicians were interrupted 7.9 times per hour, and 28 clinicians prescribed 239 medications, with 208 errors noted. Prescribing errors significantly increased when physicians were interrupted (rate ratio [RR] 2.82) or multitasked (RR 1.86). Poor sleep resulted in a more than 15-fold increase in error rate (RR 16.44). Higher working memory capacity (WMC) reduced errors, with a 19% decrease for every 10-point increase in WMC. Factors like workload, gender, and preference for multitasking did not affect error rates. The study highlights that interruptions, multitasking, and poor sleep negatively impact performance, raising concerns about the prevalence of these behaviors in clinical setting.

6. Loertscher L, Wang L, Sanders SS. The impact of an accountable care unit on mortality: an observational study. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2021;11(4):554-557. Published 2021 Jun 21. https://doi.org/10.1080/20009666.2021.1918945

This study aimed to reduce mortality and achieve zero preventable deaths through an interprofessional Accountable Care Unit (ACU) model with nurse-physician leadership, geographic localization, and daily interdisciplinary bedside rounds. Over six years and 12,158 inpatients, risk-adjusted mortality significantly decreased in the second year post-implementation (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.58), with similar improvements in Year 3. Unexpected deaths reached zero by Year 3 and remained below pre-implementation levels in Years 4 and 5. However, by Years 4 and 5, overall mortality returned to baseline. The study highlights the potential of ACUs to reduce mortality but emphasizes that ongoing effort is needed to sustain improvements amidst real-world challenges.

7. Williams A, DeMott C, Whicker S, et al. The Impact of Resident Geographic Rounding on Rapid Responses. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(7):1077-1078. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05012-8

This study examined the impact of geographic localization and interdisciplinary team rounding (IDTs) on rapid response rates at a hospital. In 2017, the Internal Medicine residency service switched to a geographic-based rounding model. The study compared rapid response rates before and after this change. Results showed a significant reduction in rapid responses (2.16% pre-intervention vs. 0.66% post-intervention). The decrease was attributed to improved communication and familiarity between residents and nursing staff, leading to quicker action on declining patients. Despite limitations, the study suggests that geographic rounding can reduce rapid response events and may be implementable in other hospitals. Further research is needed to confirm these findings and explore other outcomes like mortality and ICU transfers.

8. Klein AJ, Veet C, Lu A, et al. The Effect of Geographic Cohorting of Inpatient Teaching Services on Patient Outcomes and Resident Experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(13):3325-3330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07387-z

This study evaluated the impact of geographic cohorting, where each physician team’s patients are admitted to a dedicated hospital unit, on patient outcomes and resident satisfaction within an academic hospital. It analyzed patient outcomes from January 2017 to October 2018 before and after transitioning to this structure. Among 1,720 patients, the study found no significant changes in 6-month mortality, hospital length of stay, readmission rates, or patient satisfaction (HCAHPS scores). However, resident satisfaction with the rotation improved significantly. In conclusion, geographic cohorting increased resident satisfaction without negatively affecting patient outcomes.

9. Southwick F, Lewis M, Treloar D, et al. Applying athletic principles to medical rounds to improve teaching and patient care. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):1018-1023. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000278

This study addressed inefficiencies in multidisciplinary work rounds at teaching hospitals, which delayed patient care and reduced teaching effectiveness. Using athletic principles, medical teams were trained in systems-based approaches, with job descriptions, clear communication protocols, and feedback. In an 11-month pilot trial, teams using this approach saw a 30% reduction in 30-day readmissions and an 18% shorter length of stay. Faculty, residents, and students reported higher satisfaction, with significant improvements in teaching ratings, though patient satisfaction remained unchanged. The new system shows promise in reducing inefficiencies and improving care quality, though adaptive leadership is needed to manage resistance to change.

10. Tang B, Sandarage R, Chai J, et al. A systematic review of evidence-based practices for clinical education and health care delivery in the clinical teaching unit. CMAJ. 2022;194(6):E186-E194. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.202400

This systematic review aimed to identify evidence-based practices in internal medicine clinical teaching units that improve clinical education and health care delivery. Analyzing 107 studies (mostly from North America), it highlighted several key practices: purposeful rounding, bedside rounding, resource stewardship, interprofessional rounds, geographic wards, allocating more trainee time to patient care or education, continuous admission models, limiting duty hours, and managing clinical workload. These practices were associated with improved educational and healthcare outcomes. The findings offer guidance for policies and staffing in teaching hospitals to enhance both trainee education and patient care.

11. Osipov, R., et al. Implementing Patient-Centered Multidisciplinary Bedside Rounds. UNC Health. https://www.med.unc.edu/medicine/wp-content/uploads/sites/945/2019/01/Implementing-Patient-Centered-Multidisciplinary-Bedside-Rounds.pdf.

12. Chand DV. Observational study using the tools of lean six sigma to improve the efficiency of the resident rounding process. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):144-150. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-10-00116.1

This study aimed to improve resident rounding efficiency using Lean Six Sigma methodology in response to duty hour restrictions. The primary goal was to eliminate waste and reduce nonvalue-added time in the rounding process, while the secondary goal was to improve rounding efficiency. The study involved pediatric and family medicine residents on a pediatric hospitalist team. The “DMAIC” (define, measure, analyze, improve, and control) approach was used, and survey data were collected from residents, nurses, hospitalists, and parents. The study implemented collaborative, family-centered rounding, eliminated “prerounding,” and standardized processes, leading to a 64% reduction in nonvalue-added time per patient (P = .005). Survey responses indicated a preference for the new rounding model. The study concludes that Lean Six Sigma offers a valuable, structured, data-driven method for improving care delivery and education.

13. Balch H, Gradick C, Kukhareva PV, Wanner N. Association of Mobile Workstations and Rounding-in-Flow with Resident Efficiency: A Controlled Study at an Academic Internal Medicine Department. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(14):3700-3706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07636-9

This study aimed to improve resident efficiency through a novel workflow using mobile laptops and modified rounding-in-flow at an academic medical center. One internal medicine team served as the intervention group using this workflow, while two other teams acted as controls with traditional batch rounding. Results showed that, although communication and computer time differences between groups were not significant, the intervention group had a higher likelihood of completing progress notes (OR 1.5, p < 0.001), non-discharge orders (OR 1.1, p = 0.01), and discharge summaries within 24 hours (OR 3.9, p < 0.001) during rounds. Survey data also indicated that intervention group residents felt more efficient at completing orders during rounds (OR 7.8, p = 0.03). The study concludes that using mobile laptops with a modified workflow can improve the timeliness and efficiency of residents’ work.

14. Ratelle JT, Gallagher CN, Sawatsky AP, et al. The Effect of Bedside Rounds on Learning Outcomes in Medical Education: A Systematic Review. Acad Med. 2022;97(6):923-930. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000004586

This systematic review aimed to determine whether bedside rounds improve learning outcomes in medical education compared to other types of hospital ward rounds. The authors reviewed 20 studies, including 7 randomized trials, all involving resident physicians and 11 also including medical students. The studies varied widely in how bedside rounds were conducted. Findings on learner satisfaction were mixed, with 7 studies favoring bedside rounds, 4 favoring the control, and 4 being inconclusive. For knowledge and skills, 2 studies favored bedside rounds, while 2 were inconclusive. Regarding learner behavior, 5 studies favored bedside rounds, 1 favored the control, and 2 were equivocal. In terms of health care delivery outcomes like teamwork and rounding time, 8 studies favored bedside rounds, while 6 were inconclusive. Overall, the evidence was considered low due to bias and variability across studies. While bedside rounds appear to positively impact learner behavior and health care delivery, further research is needed to identify how to make them more educationally successful.